Our Understanding of Chocolate Flavor May Need a Rethink

New research challenges old ideas about what influences the flavor of chocolate.

Prior to joining the University of West Indies’ Cocoa Research Centre, David Gopaulchan says he never had much interest in chocolate. That all changed with his first sample from a local farmer.

“It was the best thing I’ve ever tasted,” he recalls. “It was cocoa, but there were a lot of fruity and floral notes. I just fell in love with chocolate at that point.”

But, for Gopaulchan, these new flavors also raised questions. Why did the farmer’s chocolate taste so distinct from other chocolate he’d tasted? Where were these fresh flavors coming from?

The curiosity stayed with him as he moved from Trinidad to the UK, to work as a researcher at the University of Nottingham. There, he received funding to find some answers – answers that would eventually challenge a core tenet of chocolate research.

Fermentation and flavor

That core tenet? That chocolate flavor is firmly rooted to its crop variety.

“Up until now, the scientific chocolate community believed that flavor in chocolate is predetermined by genetics,” explains Gopaulchan. “So, depending on the varieties, you get different flavor outcomes.”

“But even back in the days when I was working at the Cocoa Centre in Trinidad, that didn't really make much sense,” he tells Technology Networks. “My colleagues would grow all these different varieties yet get the same flavor which wasn't matching the literature.”

Contrary to the prevailing genetics theory, Gopaulchan had his own suspicion on

what was really influencing chocolate flavor: fermentation.

“It’s one of the first processing steps to make chocolate,” he explains.

This fermentation process relies on microorganisms like yeasts and lactic acid bacteria to break down flavor precursors within the bean into new, more palatable flavor compounds.

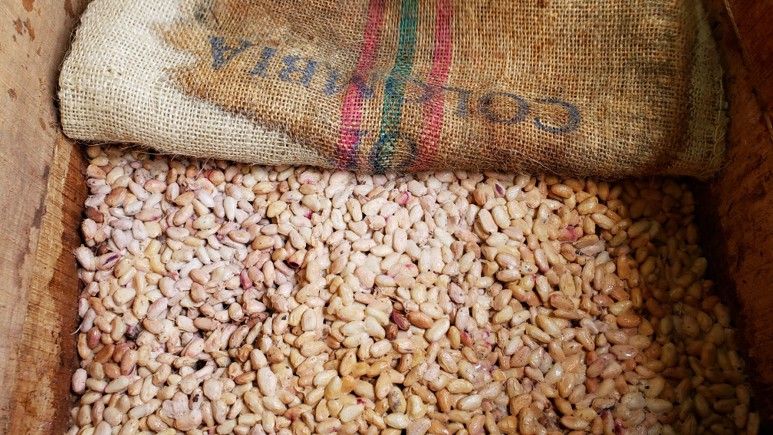

“The farmers grow the trees then harvest the fruits twice a year,” Gopaulchan says. “They then get the beans out and ferment them in boxes or baskets or just heaps on the floor; they just let the beans sit for maybe five to seven days.”

Cocoa beans lying out in Colombia. Credit: David Gopaulchan.

To test his suspicion that these microbes – not the crops’ strain – are key to chocolate’s flavor, Gopaulchan and his colleagues at the University of Nottingham visited three cocoa farms in Colombia to see if the farmers’ fermentation methods – and their chocolate – were any different.

A Columbian experiment

“We selected three farms in Colombia that are well known for having very different flavor profiles,” Gopaulchan explains.

“We did a lot of DNA sequencing of the fermentation, mainly looking at the microorganisms that were growing during the fermentation.”

Many of these microorganisms turned up across all three farms. During the first 24 hours of fermentation, most cocoa beans tended to become enriched with Erwiniaceae bacteria and depleted in Enterobacteriaceae and Pectobacteriaceae species. Acetobacteraceae then tended to become the dominant bacteria species past the 24-hour point.

One farm’s beans, however, told a slightly different story. These beans, grown and fermented in Antioquia, Colombia, contained significantly more Acetobacteraceae bacteria in the first 24-hour period than beans from the other two farms, and much more Bacilaceae bacteria after the 72-hour mark.

To find out why this farm appeared to host different levels of bacteria, Gopaulchan and his team turned their DNA testers to the surroundings, and found some bacterial matches.

“Interestingly, in all three locations, we found that these microbes were actually coming from the environment,” he says. “We detected these microbes being present in the soil, on the surface of the leaves of the plant, the surface of the pod. The microbes were even coming from the hands of the farmer; they were inoculating the beans.”

The most significant source of microbes, though, was the wood of the crates the beans were stored in.

White cocoa beans in a crate. Credit: David Gopaulchan.

“There was a reservoir of microbes in fermentation boxes,” Gopaulchan continues. “So when [the farmers] put the next batch of beans in, those microbes would then inoculate the next round of beans.”

“Essentially,” he says, “the box became a memory of what was happening from before.”

These memory boxes, says Gopaulchan, are the real deciders of the beans’ microbial communities – and thus, the deciders of their changes in temperature and pH during fermentation – and thus, he says, the key determinants of their eventual chocolatey flavor.

Chocolate and bacteria

For the beans’ ultimate test – the taste test – Gopaulchan and his team prepared cocoa liquors from the fermented beans of all three farms. These drinks were then given to a tasting panel.

Consistent with their similar fermentation patterns, the liquors from the first two farms (in Santander and Huila) shared flavor attributes with cocoa grown in Madagascar. In contrast, the panel thought the Antioquia liquor tasted more like cocoa grown in the Ivory Coast and Ghana.

These opinions concur with Gopaulchan’s hypothesis: that microbes are key drivers of chocolate flavor – the Antioquia chocolate, with its different ratios of bacteria and its different levels of pH during fermentation, also had a different flavor than the other chocolate liquors.

However, taste tests are still subjective; a different tasting panel might categorize the liquors differently. To get some more robust data on how the flavor of the beans differed, Gopaulchan again looked to DNA.

“We were able to take environmental DNA and then assemble genomes of these microbes,” he explains. “We were then able to identify the genes that were present with them and start modeling the interactions between these microbes, so we could predict if it can utilize sugars or utilize certain proteins or produce some sort of fats.”

With this level of genetic insight, Gopaulchan and his team were able to trace the development of the beans’ respective flavor compounds.

“These [compounds] are flavor precursors that would ultimately turn into the volatiles that we detect in chocolate,” he says. “The microbes themselves were producing volatiles that were adding to the overall flavor. So genetics and microbes were coming together to give you this flavor.”

For Gopaulchan, this case study not only challenges past assumptions in chocolate research – that cocoa variety ultimately determined flavor – but shows a potential future for the field: custom inoculated beans.

Microbial infusions

“This group of microbes is essentially a proof-of-concept that we’re able to create a flavor profile for these beans,” says Gopaulchan. “But it opens up the door for going even further, potentially creating a lot more different flavor profiles and engineering flavors moving forward.”

“In many ways,” he says, “it’s going to be a bit of a revolution; it’s going to shake things up a bit because it opens up the door for recreating flavors, or even creating flavors that don’t already exist. It also opens the door for exploring other flavor profiles from different regions.”

This latter potential, Gopaulchan warns, could come with upheaval, though.

“I’m not sure how the industry is going to feel about that, because for some locations their flavor profile is their identity,” he says. “So, I sense that they may not be too happy.

“But I think it's a strength for us is we’re going to have consistency. In these locations, [the farmers] get variability,” he adds. “But, by controlling the microbes […] every single time you’re going to get that taste.”

“We may even develop a standard inoculum that a company can use with their farmers,” he suggests. “So [the companies] could work with the farmers, give them this inoculum and say, ‘We need you to inoculate your beans with this and let the fermentation happen and then we will purchase it.’ Maybe that’s something that [the industry] could also adopt.”

These adopters, says Gopaulchan, are more likely to be larger companies who sell “bulk chocolate” to accessible vendors, like supermarkets. The smaller companies selling pricier, “fine flavor” chocolate will likely stick with their marketable aesthetics of independent farmers with agricultural traditions.

Both types of traders, however, still face the same blight of climate change.

Chocolate and climate change

“The problem of climate change is massive,” says Gopaulchan. “It’s devastating the industry.”

This devastation is two-fold. Extreme weather variations are making once-reliable locations for cocoa-growing more adverse environments for the crops but more receptible to their pests and diseases.

“A lot of it is heat and drought,” Gopaulchan summarizes. “But this is coupled with diseases, because now you’re seeing diseases.”

“Cocoa requires a lot of water; it’s a very thirsty plant,” he continues. “So climate change is dropping production, because the fruits are either not developing or being aborted. That's leading to drop in yields. But then also we have a disease called cacao swollen shoot virus in West Africa. It’s devastating. It’s just wiping them out.”

Initially, one might not consider Gopaulchan’s research relevant to this cocoa crisis – the microbes within cocoa pods don’t have much use if those very pods wither in a drought.

Yet Gopaulchan’s proposed microbe inoculations may just help save underdeveloped pods from what meagre flavor they managed to develop.

“In a pod that has very little water during its development has very little pulp inside,” he explains. “The farmers then harvest those beans and try to ferment them, but [the pods have] skipped the yeast stage and gone straight into the acid-producing stage, and that results in your beans being very, very sour. The chocolate is horrible.”

“It’s hard for the farmer to control something like that. How are they going to control that? How are they going to fix that?”

Perhaps, one day, with a syringe and a standardized top-up of flavorsome bacteria.